Low-Key Wildlife Portraits – Part 2

- George Wheelhouse

- Aug 23, 2013

- 8 min read

Updated: Feb 27, 2022

A few weeks ago, I wrote a blog post about the concept behind my low key, “on-black” photography project.

This time around, I’m going to talk about how I produce these images, and what sort of processing is involved.

2022 Update: Since I wrote this post about my low-key nature photography project, I've written many others, and also added an On Black web gallery.

Introduction

I should start by saying that this style is not something I’ve invented myself – it’s been a popular portrait theme for decades. But I have innovated the processing-side independently of others, and developed this technique for using it in wildlife portraits by myself. It’s been a case of trial and error, over the last few years to get the results I do now. And I don’t consider it finished either. I’m sure I can continue to improve. Who knows – maybe one day I might even be able to get some of these animals into a studio for some properly lit portraits :-)

The amount of post-processing required for these images really depends on the original shot. Most importantly;

The nature of the light hitting the subject,

And how the subject is differentiated from the background.

As you would imagine, the ideal situation for taking the original photo would be as close to the lighting conditions that I intend to simulate as possible – so a softly side-lit subject in front of a dark or shaded background. Also bear in mind that the camera sensor has a vastly inferior dynamic range compared to the human eye, so what looks like shade to us, can render as black if the camera is set to expose for the subject. This concept is crucial in many circumstances. But since all my on-black photos are sun-lit, I have to stay flexible and work with whatever lighting conditions I get on the day.

There are two main ways of distinguishing the background from the foreground in-camera. One is with light (this is ideal, as described above), and the other is with focus. By keeping a shallow depth of field, I can ensure that the background is thrown out-of-focus, which makes the job of blacking it out far simpler because it leaves the subject with a clearly defined edge.

OK, so, next I’m going to talk a little about the equipment required for these photos.

Then I’m going to run through the step-by-step processing of my most recent photograph – a pelican from St James’s Park in London.

Then I’ll show some more before & after shots, and explain the unique processing that these shots required.

EQUIPMENT

Clearly the first thing you need is a camera. I shoot with a Nikon D800, but any camera will do. I’m not going into the pros and cons of different makes & models, but from here on in, I’ll assume we’re all using a dSLR, and shooting RAW.

If you shoot with a dSLR, then you’ll need a lens in the region of 200mm-400mm. I shoot with a fixed-length 300mm lens. Again, this is not the place for lens talk, but suffice to say you get what you pay for, even more so than with the camera body.

When I first tried this, I was shooting JPEG, and editing in Adobe Photoshop Elements. I then started shooting in RAW format, which makes a world of difference. But this left my workflow as a rather convoluted [RAW > Adobe Photoshop Elements Catalog > Adobe Camera Raw > Adobe Photoshop Elements Editor]. I’m now using Lightroom (4) to process all my images, and it’s also far better for these on-black images than Photoshop. My workflow is now just [RAW > Lightroom] (+ export to jpeg for online). Another reason that Lightroom works better than Photoshop for this process is that instead of painting in black (with some level of opacity), Lightroom enables me to apply brush strokes of exposure adjustment – which does a far better job of simulating lighting than painting in black. I also love the “Auto-Mask” feature of the Adjustment Brush tool in Lightroom.

Another great addition to my workflow is my Wacom graphics tablet. I have the humble Bamboo model, which is pretty basic but it’s all I need, and makes the brushing process simple, intuitive, and more accurate. This is really what enables me to add the finer light and shade as I would in a drawing many years ago.

Lastly, you need a decent, reliable (calibrated, if possible) monitor. Using a laptop monitor simply isn’t going to cut it. With the exception of the high-end Apple laptops, most laptop monitors are pretty poor for viewing photos. Because each monitor will display images differently, you need to know that you’re using one which is correctly set up – not too bright, not too dark. Adjusting the subtlety of shading in a low-key image using a low-contrast over-brightened monitor will leave your photos looking shoddy to everyone but you.

STEP-BY-STEP : A RECENT EXAMPLE

1. OK, so we’re starting with an unmodified RAW image of a pelican straight-out-of-camera…

My decisions when shooting were as follows:

Use 300mm lens so I don’t have to get too close, and I’m able to compress the scene against a smaller background, meaning I’m more likely to find something dark / plain. Using a wider lens would mean taking in more of the scene, and more likely to include more complex background. 300mm also allows me to;

Keep a shallow depth of field – by using 300mm focal length and by shooting at f/5. This lens has a max aperture of f/4, but f/5 is slightly sharper, and also allows for more DoF in the subject too. You can see that the back end of the wing feathers are just out of focus here, simply because they’re closer than the focal point (the eye). If I’d have shot at f/4, the nearside feathers would have been even more blurred. Similarly, if I’d had stopped down to f/8 for a better DoF in the subject, then the background foliage would have been in focus, which very much complicates the process of separating foreground & background.

Use as fast a shutter speed as possible, without compromising the ISO too much. This is usually the rule for wildlife.

Create a disparity in brightness between subject and background. Fortunately, the pelican is a fairly light colour, meaning that I didn’t need a very dark background, and even the shady foliage is significantly darker than the white pelican.

Composition. As ever I needed an interesting composition. I was hoping to get some of the pelican from straight-on, but that’s easier said than done. In this case, I like the S-curve of the neck, head, and beak, and there’s something about him turning his back to us, that make it seem like he’s complicit in this pose.

Also note that this was taken in overcast lighting, which doesn’t create too much contrast. White subjects can be very tricky to expose for, so this kind of lighting is ideal for the subject really. In bright sunlight, this would probably have come out looking quite flat and wouldn’t have made the cut.

2. Convert to Black and White…

3. Basic processing, to deepen shadows and enhance contrast…

This step varies from photo to photo, and you need to keep an eye on the histogram and the image to produce a satisfactory result. I start by setting the Contrast, Highlights and Blacks. Then tweak the Shadows and Whites to get the final result.

Notice that we almost have the subject on-black already, without needing any brushing / painting. This means that we got a good photo to start with, and usually signifies that the result will be simpler and more realistic than one which requires a lot of localised brush adjustment.

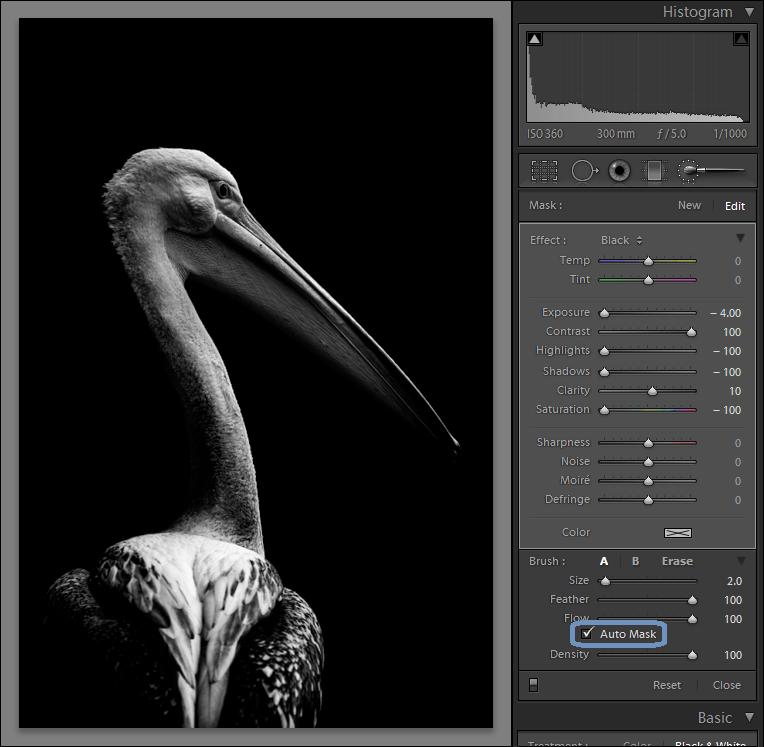

4. At this stage, I used a ‘black’ Adjustment Brush to completely mask off the remaining highlights in the background, so that nothing is visible.

Note that the “Auto-Mask” feature is particularly useful here to accurately mask out the background without effecting the subject. The greater the difference between subject and background (see intro above) the better the Auto Mask will work.

Sometimes I need to brush in some exposure reduction around the edges of the subject, if the original photo was harshly lit. This prevents the kind of hard edges which are a total give away that the original shot wasn’t low-lit. But since this one was taken in a nice soft light, that step wasn’t required here.

5. Just some final tweaks to Whites and Clarity.

Note how the histogram now just touches the right-hand (highlights) edge, without actually over-exposing.

6. The final step in this case was to use Photoshop to increase the canvas size, and transform the image into landscape orientation, which I think works better for this composition. And this is the final result…

SOME MORE BEFORE AND AFTER PHOTOS

Just to illustrate what kind of original I worked with to produce some other images…

Tawny Owl

I never liked the background in this shot, which is otherwise a nice tawny owl portrait. After I painted out the background to black, I had to soften the edge of the outline with the Lightroom Adjustment Brush. It’s not the perfect shot for it, as the background is fairly bright, and there’s no interesting shadow on the subject. But it just about works. When painting in shade like this, it’s important to have an idea of where your imaginary light source is, and to be consistent to that light source – in terms of both angle and softness. I remember finding that reducing the Blacks more than usual also gave the shadow a more realist look in this shot.

Bengal Tiger

I can’t stand to see cages in any photos, so I had to do something with the background here. If I’d have been able to shoot at a wider aperture, or longer focal length, I could have blurred the background completely, and produced an appealing photo on a soft green background. But that wasn’t an option for me given the lens I was using at the time, and the restriction (for my own safety!) in my distance to the subject. So I decided to render the background black, to keep the focus of the image on the subject, and off the background. I also cropped to just the head-shot, which I think works better. It seems a shame to lose the gorgeous amber colouration of a tiger, but I thought the final image looked better in black and white.

Zebra

I took this one from a bridge, as the zebra passed underneath me, which creates a really unusual perspective. Again, the background probably isn’t dark enough here, but the shallow depth of field easily clarifies subject and background, and makes it easy to darken just the background, using the Auto-Mask Adjustment Brush. Switching to black and white was an easy decision here, as it’s a very attractive presentation for the distinctive pattern of a zebra.

Finally…

Well that’s my processing workflow for these on-black portraits. They require some forethought, planning, an artistic eye, and some time and patience in processing. But the results can be very original and striking.

I’m sure over time, more and more people will be producing photos like this, so my aim is to stay ahead of the curve, and keep innovating, and creating original work. I think my style will remain in my work, and should continue to distinguish it from others who shoot the same way – just as most photographers have their own recognisable style, whatever subject they shoot.

You can see my best fine art nature photography here, and I now have a collection of low-key portraits on black, high-key portraits on white on this website, many of which are available in print.

If this post was of use to you, please share on twitter, facebook, etc, or feel free to leave a comment below. Thanks :-)

–

George